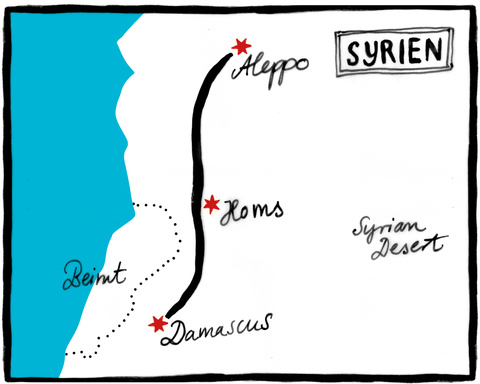

The following text is an article that was published in the quarterly Sufi magazine "Heart & Wings" in spring 2008. It tells from a journey I made with a friend to Aleppo and Suhrawardi's dargah. Since then has happened a lot. Some years later we met Shaykh Jamal in Istanbul, where he had fled with his family due to the Syrian civil war. He couldn't tell us, what had become of Omar, the mosque keeper, and what would be the present condition of the mosque and the dargah of the Shaykh al-Ishraq.

Two Austrian SOI-members visited the dargah of Shihab al-Din Yahya al-Suhrawardi, the great master of light, in Syria. Here is a report about their experiences with the local community.

"One Friday after prayer at the end of Dhu'l Hijja 587 (January 1192), al-Shihab al-Suhrawardi was brought out dead from prison in Aleppo, and his disciples dispersed." In these plain terms the historian Ibn Khallikan described the death of the Shaykh al-Ishraq. ¹) We do not know who these disciples were. We do not even know how exactly this great Sufi saint died. Some report he was beheaded because of his brave, brilliant, and unconventional teachings. Others report that he was put into prison and starved to death. But one thing is certain: Shihab al-Din Yahya al-Suhrawardi has had a decisive impact on Sufism and Islamic philosophy up to our days. He also influenced the teachings of Hazrat Inayat Khan to a great extent. Pir Zia: "The Shaykh al-Ishraq was very special. He was not part of a certain silsila but gained his wisdom from his contacts with great prophets and

philosophers at the plane of Hurqalya, the plane of creative imagination."

Now on december 24th, 2007, my friend Ursula V. and I arrived at that very place in Aleppo, Syria, where Suhrawardi was buried 800 years ago. The remains of the old city wall are still visible in the ditch on the other side of the street, in front of the mighty Sheraton Hotel. But the fields outside the wall disappeared a long time ago and made way for the Christian Quarter. The dargah is now part of a small mosque at a side-entrance of the police headquarters.

We ask one of the armed policemen who keeps guard for directions.

“Yahya Suhrawardi? Shaykh al-Ishraq? Never heard of him.”

But just around the corner, in small Salibeh Street, we find a poor signboard and the inconspicuous green door of the mosque. It is closed. We are told that we have to wait for the muezzin who will come within the next half-hour.

The outside of the building is ugly. But when you get inside, you find an amazing, quiet, lovely place, filled with enormous power and light and love. The atmosphere is so beautiful that you forget about small things like the desolate ceiling, the blots on the wall and the white plastic chairs that are stationed around the grave-site. The presence of the Shaykh al-Ishraq is overwhelming.

Narrow road to the mosque

It is a mosque only for men. We were lucky that we arrived before the morning,prayer which is normally poorly attended. And fortunately it was Omar Khadim, the muezzin, whom we met first. He is the one who unlocks the mosque before prayer times, who calls for prayer, who cleans the mosque, who cares about fresh air and heating and cares for the house in general. He speaks only Arabic, as do most of the Syrians, which makes communication difficult. But he is such a loving and openhearted man, the very soul of this little mosque. He let us in and lets us sit in front of the tomb before and after prayertime. And when he realizes that we are coming back every day, he starts to come earlier and seems to enjoy it. Somehow we have the feeling that each day the site is becoming cleaner and better smelling.

Suhrawardi's dargah (tomb) within the mosque

But two women in a men's mosque cannot stay unnoticed, even if we always are on the balcony during the prayer. Every day more men come to join the morning prayers; some of them look very welcoming, others quite grim. On the fourth day two men address us in poor English. Do we know who is lying in the tomb? Yes, we know. They seem surprised but nevertheless insist that women are not allowed in this mosque. Omar tries to defend us, so we are not cast out immediately. But it is clear that these men (one of them led the prayer) will not tolerate our presence any longer. We decide now it is time to contact the local spiritual leader, Shaykh Jamal Hoot.

Omar tells us that the Shaykh only attends the afternoon and evening prayers. And he brings us to a small copy shop nearby. The owner is a close friend and obviously a disciple of Shaykh Jamal. He calls for a translator (who too is a friend and disciple of Shaykh Jamal), and soon the Shaykh himself appears.

It is a delicate moment. Pir Zia had encouraged us to look for ways to improve the condition of the dargah. This task, we thought, could only be fulfilled in cooperation with the local community. But how could we express our interest in the Shaykh al-Ishraq and the condition of his dargah without appearing like interlopers and presumptuous Europeans? We try to choose our words very

carefully. Fortunately the Shaykh turns out to be a very openhearted man. And he remembers very well the visit of Zumurrud, our spiritual guide. She had visited Suhrawardi's dargah seven years ago and obviously made an excellent impression on Shaykh Jamal.

He invites us for dinner and seems very interested in our Sufi Order. He asks us about our gatherings at home and is very delighted when he hears that we always start with the invocation. He wants to have this invocation translated word by word. He also tells us about adab, dying before death, and the importance of love and surrender. In between his friend, the translator, uttered some remarks about "God who perhaps was a She and not a He, who knows?"

This evening we also accompany the Shaykh to the evening prayer in the mosque, and Omar beams of joy and pride when he sees us. And on that day we are not the only women at the balcony. All of a sudden another woman appears and prays together with us. It was amazing how fast the news of our presence has spread.

After an interruption of three days in Damascus, we follow Shaykh Jamal's invitation to meet him again at the mosque. But now we are confronted with a rather unpleasant surprise. We are no longer allowed to take a seat on the balcony. This time we are asked to go into a small, ugly chamber during the prayer - not by the Shaykh himself, but by some of his men. From now on we always have to go into this cold and isolated chamber at the back of the mosque. Fortunately our friend Omar still allows us to sit in front of the tomb when the mosque is empty.

This is the uncomely "women's room" in the mosque

We only could guess, but it seemed there had been some discussions about women in the mosque. The men knew that we would leave soon. But it happened again that our presence attracted other women to the mosque. To move us into this separated room seemed to be a compromise between the hardliners and the tolerant ones - we were allowed to come to the prayer, but out of sight of the men. Shaykh Jamal stays as friendly as ever, waits for us in front of the mosque after prayer, invites us to his home and introduces us to his family.

On our last day in Syria, Shaykh Jamal invites us to a meal in the mosque, in the ugly little “women's room” which also contains a small kitchen corner. We sit together with his closest disciples; one of them was the man who had tried to cast us out of the mosque. Now he serves us, eats with us and tries to put the best pieces into our bowls. Also a guest from Russia is there. This time we have a nonprofessional “translator” which makes communication more difficult. We understand only parts of what the shaykh says but realize that he speaks about different nationalities and the importance of tolerance. Then he adds prayers and the invocation of some wazaif. We exchange presents and get several gifts from the Shaykh and his followers - most of them spices and Syrian candies. He also adds a gift for Zumurrud and utters his regret that he can not send a gift to Pir Zia too. And he tells us again and again that every member of our organisation is most welcomed at his home. If anybody is going to Halab, he says, even groups of five up to ten people, they shouldn't go to a hotel but contact him and be guests at his house.

Herewith I'd like to pass on his welcoming words to all of you, hoping that this will be the seed for a growing friendship between East and West. May Pir Zia's wish be fulfilled that we can do something for this powerful place where Shihab al-Din Yahya al-Suhrawardi is buried. And may we give something back to the Shaykh al-Ishraq who left to us such a beautiful heritage.

Ingrid Nurunnahar Dengg

______________________________________________________________________________________

¹) John Walbridge, The Leaven of the Ancients, Albany/N.Y. 2000, p. 211.